Virginia becomes 16th state to pass Heirs’ Property Act

In the years between 1920 and 2017, the number of Black-owned farms in the U.S. dropped from more than 900,000 to 45,508; their acreage shrank from almost 19 million to just 2.5 million. Involuntary land loss is one of the many insidious factors. And our country’s broken way of dealing with land that’s informally passed down without a will is among the top causes of involuntary land loss.

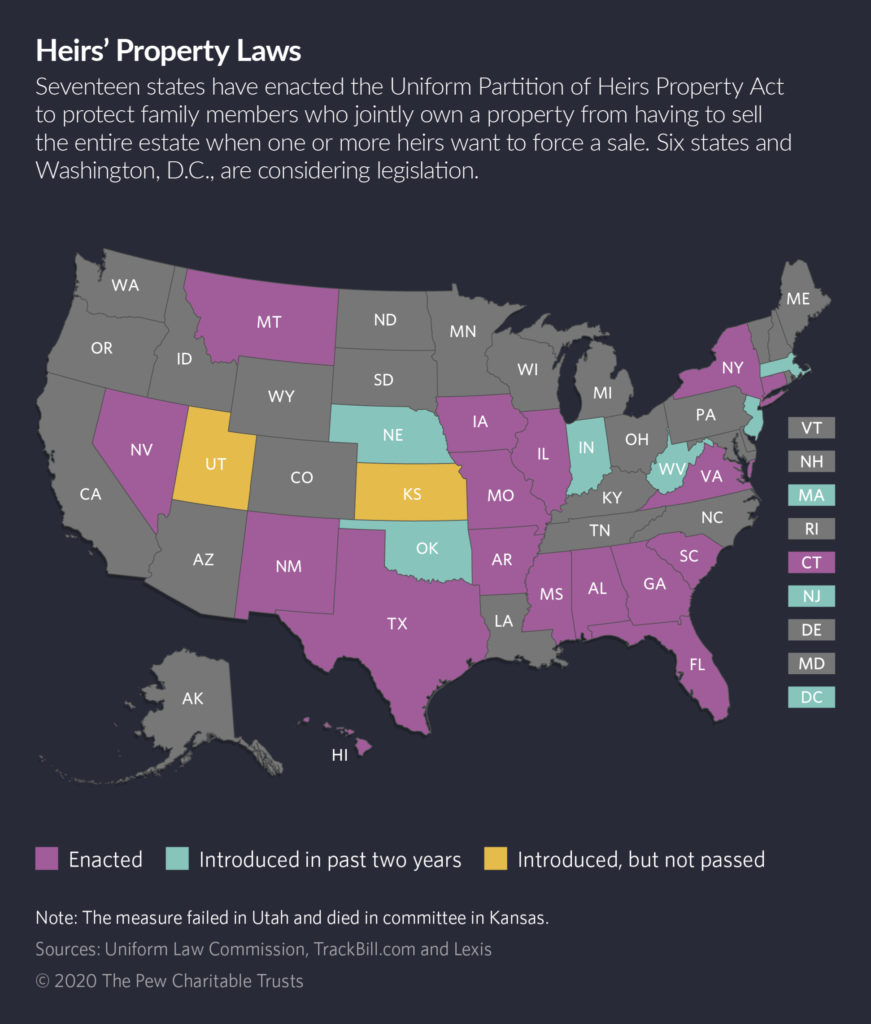

That’s why in 2020, Virginia proudly became the 16th state to pass the Uniform Partition of Heirs’ Property Act. It’s a bill that Virginia Secretary of Agriculture and Forestry Bettina Ring calls, “an important first step toward ensuring more Virginia families can stay on the land they have stewarded for generations.” Rockingham County’s Blakey Farm, the ancestral home of Virginia native and basketball legend Ralph Sampson, was the perfect setting for Gov. Ralph Northam’s ceremonial signing of the bill; just three weeks prior, Sampson’s family received the final court document ending their difficult, five-year battle to hold on to the family’s farm.

Sampson remembers precisely the day it all started— September 23, 2015—he got a call from his mother, Sarah Blakey Sampson. “The sheriff had just come to the house in Harrisonburg and served her papers from my uncle, her brother and his wife. It says ‘Blakey v. Blakey,’ and she wants to know what’s going on,” Sampson recalled during a recent presentation for the Virginia United Land Trusts.

Sarah was the 10th of 12 children born to George and Josephine Blakey, who bought a Rockingham County farm next door to what’s now Massanutten Resort, from a white man 80 years ago for less than $7,000. “He only sold it to my grandfather because he thought my grandfather could farm it well with nine boys to help him. My grandparents raised 12 children there, grew and produced agricultural products, and lived off the soil,” Ralph said during the presentation. Like many first-generation landowners and Black families in the South, land ownership for the Blakeys represented identity and opportunity and meant economic security and stability for future generations of family.

When George and Josephine died without a will, their land informally passed on to their 12 children and their children, becoming what’s known as “heirs’ property.” Now, one of those heirs had blindsided the rest of the family with a lawsuit, intending to force the sale of all of Blakey Farm.

This is, too often, the unfortunate story of heirs’ property. Generation after generation of heirs, no matter how distantly related, if they live on the land or across the country, or if they’ve ever even heard of the original landowner, share ownership of the land, called “tenancy in common.” In the Southeast, where heirs’ property is often rural land first acquired by African-Americans after the Civil War, that means heirs can number into the hundreds. A disastrous legal construct called a “partition action” allows any one of these co-tenants to force the sale of the entire property, against the wishes, and sometimes even without the knowledge, of the others. Involuntary land loss is the result.

A disastrous legal construct called a “partition action” allows any one of these co-tenants to force the sale of the entire property, against the wishes, and sometimes even without the knowledge, of the others. Involuntary land loss is the result.

“One example of when this becomes a problem is an outside developer approaching one of these distant family members, acquiring their share, and then filing a partition action to force the sale of the entire property, often at a value far below the market,” Ring wrote in a widely-distributed article earlier this year.

Fighting a partition sale is nearly impossible, particularly because most heirs’ property lack a clear title. Without that, co-tenants are ineligible for private financing and federal loans for mortgages to build houses, buy farming equipment, or make improvements to the property. As a result, they are often “land rich and cash poor.” Developers often exploit that economic hardship or appeal to a family member’s desire for profit, buy their share of the land for a fraction of its value, and then petition the court that the ownership structure is devaluing the overall property. The judge can—and most often does—order the land be sold, usually at auction well below market value, without any consideration of the heritage or history of the land or any human circumstance. The developer makes a huge profit, while the family loses everything.

“Imagine if your family has lived on the same piece of property for a century or more, and all of the wealth you have accumulated is tied to the hard work and the sweat you have poured into its soil. Now imagine that in nearly an instant, because of a broken legal construct, that land and those generations worth of hard work vanishes out from underneath you,” Ring said.

For Sampson’s family, the threat didn’t come from a developer, but another family member—Ralph’s uncle, who enlisted the support of some nieces and nephews. Of the ensuing five-year battle to hold on to the family farm, Sampson said, “It’s a nightmare. It’s a true nightmare.”

Ralph’s family was introduced to the Black Family Land Trust, a North Carolina-based nonprofit dedicated to the preservation and protection of African-American and other historically underserved landowners assets against involuntary land loss. BFLT advised the Blakey family along the way and helped them assemble all they needed to fight the partition sale.

“You have to bring the whole family together, and the family has to agree to what they want to do,” said BFLT Executive Director Ebonie Alexander. “Ralph needed a good lawyer they could trust, because that property is incredibly valuable where it is located and there are often conflicts of interest. They had to build a family tree, get an appraisal, determine who wanted to stay and who wanted to sell, and determine how much money they needed to buy out those who wanted to sell. And they had to constantly keep the other family members informed and understanding the process,” Alexander said.

Tracking down every living heir can be an expensive and time-consuming process, as paperwork on Black genealogy is often thin, deeds are sometimes in the family’s slaveholder’s name, and many legal documents use nicknames, lack surnames, or omit names altogether. “Ralph’s family was still very much connected and was only two generations away. When you get to three and four generations away, it’s much harder. Heirs may have no connection to the land, and they usually have a disproportionate idea of what the land is worth,” Alexander said. The process can easily divide a family and drain its resources until they have nothing left.

“The cousins might not ever speak to me again. There’s one aunt that will never mend those fences. I used to spend two weeks every summer with my cousin at their house and he used to come to my house and spend two weeks with me, and now she tells me I can’t talk to my favorite uncle anymore,” Sampson recalled during his presentation.

Five years, competing appraisals, countless court dates and delays, a roller coaster of losses and wins at circuit and state supreme courts, eventual mediation, and several hundred thousands of dollars in attorney’s fees later, George and Josephine Blakey’s farm remains intact. Sampson, his mother, and the family members who wanted to keep the farm were eventually able to buy out the other side, and they formed an LLC that will provide forestry income for the family, serve as an educational working farm, and provide historic and cultural resources for visitors from Massanutten Resort going forward.

Most heirs’ property owners aren’t so fortunate. The 2001 U.S. Agricultural Census estimates that in the South since 1969, about half of all Black-owned land loss was the result of partition sales.

Most heirs’ property owners aren’t so fortunate. The 2001 U.S. Agricultural Census estimates that in the South since 1969, about half of all Black-owned land loss was the result of partition sales. Across the nation, 76 percent of Black Americans don’t have a will and an estimated 30 percent of rural properties may lack clear title. Heirs’ property loopholes have also made victims of Native Hawaiians in Hawaii, Latinos along the New Mexico-Texas border, white Appalachian families, and others without access to legal services and estate planning knowledge and tools. “Heirs’ property is not based on geography, race, or gender, but simply if you die without a will or don’t have the resources to resolve generational ownership,” Alexander said.

The Heirs’ Property Act gives these families help in the face of a partition action. “The new law preserves the rights of co-tenants to sell their interest, but also ensures that other tenants have the proper due process,” Ring said. Specifically, co-owning family members now have the first option to buy out those who want to sell, and judges must consider cultural, sentimental and historical significance of a property, as well as livelihood and consequences of eviction, before ruling to sell it. If the property is to be sold, it must be sold on the open market to ensure families receive a fair sale price.

The unanimous passage of the Heirs’ Property Act is the culmination of more than a year’s work by the Black Family Land Trust, which led a broad coalition of Virginia’s United Land Trusts, including The Piedmont Environmental Council, and others. The bipartisan bill was sponsored by State Sens. Frank Ruff (R-Mecklenburg) and Jennifer McClellan (D-Richmond), and Dels. Patrick Hope (D-Arlington) and Michael Webert (R-Fauquier). PEC assisted in discussions with the Virginia Bar Association and Uniform Law Commission and played a key role in lobbying for the bill prior to and during session.

Of the historic bill signing, Sampson said, “It was a special moment for me and my family, and especially for my mom. It was the most wonderful thing in my life that she could know the place she grew up is not going to go anywhere. It was a dream come true.”

This article appeared in The Piedmont Environmental Council’s member newsletter, The Piedmont View. If you’d like to become a PEC member or renew your membership, please visit pecva.org/join.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Webinar – Keeping Land in the Family

Watch our webinar Keeping Land in the Family to learn more about heirs’ property, the basics of the new Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, and what it might mean for you and your family. This event was held on November 17, 2020 and was co-hosted by the Black Family Land Trust, Virginia’s United Land Trusts, Virginia Eastern Shore Land Trust and Capital Region Land Conservancy.

Heirs Property FAQ:

- What is Heirs Property? Heirs property refers to land owned by multiple people, each who inherited their share. Owners of heirs property are considered tenants in common.

- How do you become an heir? You become an heir either by being named a beneficiary in a will or if there is no will, when property passes to you via succession. For example when a landowner dies without a spouse, their children inherit equal rights to the land.

- What are the rights and responsibilities of an heir? Each heir inherits a proportional share of the whole property, has equal rights to full use and possession of the real property, is legally responsible for taxes and other real property-related expenses, may transfer interest in the real property to another heir or outsider, may seek a partition of the real property, and must agree to any major decisions about the real property.

- What are the problems and challenges with Heirs Property? Heirs of heirs property lack clear title to the land. Those living on heirs property are at increased risk of forced sale and eviction. Heirs face difficulty qualifying for agriculture loans and government programs including loans and disaster relief.

- How can heirs use property as an asset? Property is often a family’s greatest asset. It may be someone’s home or legacy. It’s a source of income. It can be borrowed against or used to leverage conservation programs. Income may come from agriculture or forestry practices even from conservation programs.

- Who does Heirs Property affect? Heirs Property disproportionately affects middle and low income families without access to affordable legal services. African Americans are more than twice as likely as White Americans to not have a will; therefore, heirs property continues to be the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss.

- What is the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA)? UPHPA “seeks to address partition action abuses that have led many Americans to lose their tenancy-in-common property involuntarily in various legal proceedings. The UPHPA preserves the right of a co-tenant to sell his/her interest in inherited real estate, while ensuring that the other co-tenants will have the necessary due process, including notice, appraisal, and right of first refusal, to prevent a forced sale. If the other co-tenants do not exercise their right to purchase property from the seller, the court must order a partition in kind if feasible, and if not, a commercially reasonable sale for fair market value.” (Alexander and Agelasto, Ensuring Rightful Property Ownership Through UPHPA, 2019).

- Who are the key players and what are the resources that are needed to navigate through this process? Family history plays an important role in understanding who the heirs are. Families will benefit from completing genealogy research back to the owner on the deed before engaging legal representation. A family tree will help prove who all the heirs are. Lawyers complete the necessary title search. Families also need to know the boundary lines of the property, determine the value of the land, and pay the taxes. Heirs may work with lawyers, mediators, estate planners, appraisers, realtors, surveyors, land trusts and conservation groups, county or city planning offices and assessors.

- What resources are available to help landowners find family co-owners or their descendants? Families can work with a genealogist to determine who the heirs are.

- How many family farms are at risk due to heirs property issues in Virginia? There is no current estimate for Virginia. However, researchers at Auburn and Tuskegee Universities estimate that there are between 150,000 to 175,000 acres of heirs property owned by people of any race or ethnicity in Southside and that this property conservatively is valued at $650 million.

Links to more information:

- What is Heirs Property? – Heirs’ Property Retention Coalition

- Keeping land intact, in farm and forestland, and in the family – Op-ed by Virginia’s Secretary of Agriculture and Forestry, Betina Ring in the Richmond Times.

- Wealth Retention and Asset Program (WRAP) – a comprehensive intergenerational program designed specifically to reduce the rate of African American and other historically underserved population’s land loss by educating landowners about: heirs property and estate planning, intergenerational financial management, conservation easements, and 21st-century options for land use.

- Ensuring Rightful Property Ownership: Keeping Land in the Family – Virginia Conservation Network 2020 legislation summary

- Why Florida Passed a Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act – Defenders of Wildlife white paper

- Heirs’ Property Act in Virginia

- Final Legislation – passed the Virginia General Assembly in 2020

- Virginia’s Approach to the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA) as Adopted by the General Assembly in 2020 – background and recommendations by David Gogal, Principal at Blankingship & Keith, P.C (pdf)

- Final Legislation – passed the Virginia General Assembly in 2020

More news:

- Black landowners will benefit from new funding to prevent land loss – ProPublica

- Black Lands Matter: The Movement to Transform Heirs’ Property Laws – The Nation

- New laws help rural black families fight for their land – Pew Trusts

- Northam Signs Heirship Bill On McGaheysville Farm – Daily News Record

- The Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act: Keeping Farm and Forestland In The Family – Virginia Biosolids Council

- Black families once lived off their southern farmland. Their descendants are struggling to hold onto it. – The Washington Post

- African Americans Have Lost Untold Acres of Land Over the Last Century – The Nation

- Continuing the legacy: Farmers face land succession challenges – AgriNews

- Hope, Rowsome and Perry: Heirs Property Act helps Black Virginians keep ownership of their land – Roanoke Times

- Their Family Bought Land One Generation After Slavery. The Reels Brothers Spent Eight Years in Jail for Refusing to Leave It. – ProPublica