When I saw “replacement” of the circa 1878 Waterloo Bridge—the oldest metal truss bridge still in service in Virginia at the time—on the Fauquier County Transportation Committee agenda back in October 2013, I knew exactly who to turn to.

Mary Root, chair of the Fauquier County Architectural Review Board, had been leading the fight to rehabilitate the also-historic Remington Bridge since 2011. Like most pony truss bridges in Virginia, the Remington Bridge was denied state status as a historic resource, making the case for rehabilitation particularly challenging, but Mary researched, raised funds and awareness, and persisted until the VDOT’s plans for the Remington Bridge changed from “replacement” to “rehabilitation.” I hoped for at least the same outcome for Waterloo.

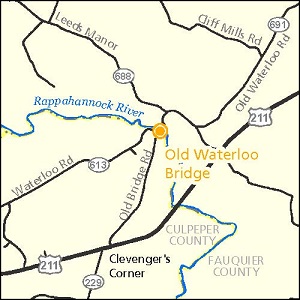

Waterloo Bridge spans the Rappahannock River, historically a major route for moving agricultural goods from the Shenandoah Valley to the Port of Fredericksburg. Known for its distinctive iron and steel Pratt through-truss, the bridge was built at a river crossing that first served as a link to a bustling canal town and later became pivotal during the Civil War. Today, it links Waterloo and Old Bridge roads in Culpeper County to Jeffersonton Road in Fauquier County. Fortunately, unlike Remington Bridge prior to Mary’s efforts, Waterloo Bridge was already designated “significant as Virginia’s oldest surviving in-service metal truss bridge” by the Virginia Transportation Research Council. I just had to spread the word and make a case for “rehabilitation” rather than “replacement.” Mary got me started.

Eight months pregnant with my first child, I was very busy that December. I gathered background information, wrote letters and sent emails, made calls, and of course, did a little nesting to prepare for my son’s arrival. On Jan. 15, 2014, VDOT officially closed Waterloo Bridge and formally scheduled it for “replacement with a modern bridge” on the VDOT Six Year Improvement Plan (SYIP). The next day, my oldest son was born and I spent my maternity leave waiting and watching to see if any of the seeds Mary and I had planted in December took hold.

By May of that year, the “Save the Waterloo Bridge” Facebook page created by students at Kettle Run High School had more than 2,500 “Likes,” and I was fielding several calls a week with questions, suggestions and stories about the bridge. The air was filled with a deep community-wide passion to save this bridge. PEC continued to push, attending meeting after meeting with VDOT and county officials. There were community meetings, a petition, yard signs, stickers, and Waterloo Bridge postcards mailed to elected officials. We even sent a recording of the rumbling sound of driving over the bridge to Virginia Water Radio for its “water sound” of the week and successfully nominated the Waterloo Bridge for Preservation Virginia’s “2014 Most Endangered Historical Sites.”

Our task was monumental, given VDOT’s pattern of delaying repairs to the point of deterioration, followed by closure and replacement or demolition of similar historic bridges. PEC raised money from Fauquier and Culpeper counties and private donors for a feasibility study that not only found Waterloo Bridge to be a great candidate for rehabilitation, but also estimated the cost of rehabilitation well below replacement cost. This pushed VDOT to do its own study and finally admit that rehabilitation could be done for around $4 million—nearly $2 million less than the cost of replacement.

When Waterloo Bridge joined Remington Bridge on the VDOT SYIP as a “scheduled rehabilitation” rather than “replacement,” we celebrated, but reservedly so. Remington Bridge had been sitting on this same list for years due to lack of funding, so this was only a small win.

Indeed, Waterloo Bridge sat on the “scheduled rehabilitation” list until 2018. That’s when Russell and Joan Hitt, longtime Rappahannock County landowners with a deep family connection to the bridge, heard the story from PEC and offered the one thing holding up the project: funding.

Mr. Hitt’s father grew up along the Rappahannock River near the village of Waterloo, on land that’s been in his family since 1802. His great-great grandfather Albert Hilleary Hitt “had to go down this road, the Waterloo Bridge, to take their grain and so forth to be ground at the mill there. It’s a long family tradition… I miss going up and down the road and across the bridge and hearing the tires rumble on the boards. It was kinda nice. Don’t have many of those today,” Mr. Hitt testified before the Fauquier County Board of Supervisors in 2016.

That crucial connection to his family’s homeplace led the Hitts to offer an incredibly generous private contribution of $1 million—roughly one-fourth the total cost. With that pledge, the rehabilitation of Waterloo Bridge was to become a reality at last.

In April 2020, Waterloo Bridge’s 100-foot-long iron truss was hoisted off its old stone abutments for restoration. Seven months later, the rehabilitated truss was dropped back into place and crews worked to prepare the bridge for reopening. On Feb. 23, 2021, years of hard work, persistence, impassioned community involvement and the generous contribution of two private citizens paid off when the Waterloo Bridge reopened to traffic for the first time in seven years.

PEC was relentless in our efforts because the situation demanded it and area residents never gave up. Today, Waterloo Bridge remains the oldest operating metal truss bridge in Virginia. Russell Hitt passed away in September 2020, and was sadly never able to see the fruit of his contribution. But I am thrilled that his children and grandchildren, area residents, visitors, and my now-seven-year-old son, can again enjoy the historic bridge that Mr. Hitt loved so much for years to come.

This article was written by Julie Bolthouse and appeared in The Piedmont Environmental Council’s spring 2021 member newsletter, The Piedmont View. If you’d like to become a PEC member or renew your membership, please visit pecva.org/join.