Over the past year, there has been a heated discussion of issues tied to growth and taxes in Fauquier County, both in the local papers and in casual conversation. In these discussions a host of terms are often used without definition. So here’s a short list of some taxes and concepts that every resident of Fauquier County should know when talking growth and taxes:

‘Service Districts’ or ‘Growth Areas’

For planning purposes the County is divided into three categories: service districts, villages, and rural areas. Service districts, also known as “growth areas”, are where the majority of the residential, commercial, and industrial growth is supposed to go.

For planning purposes the County is divided into three categories: service districts, villages, and rural areas. Service districts, also known as “growth areas”, are where the majority of the residential, commercial, and industrial growth is supposed to go.

In Fauquier, the Service Districts include Bealeton, Marshall, New Baltimore, Opal, Remington, Warrenton, and the three smaller Village Service Districts of Catlett, Calverton, and Midland.

By maintaining its rural areas and focusing most development in our service districts, Fauquier has managed to keep infrastructure and public service costs relatively low.

Comprehensive Plan

Every locality in Virginia must express its goals in a Comprehensive Plan, a twenty-year vision which must be reviewed and/or revised every five years. The Comprehensive Plan is the community’s most important document regarding land use, growth, development, transportation, and resource utilization. It projects needs and trends over the next twenty years and lays out the community’s road map for the future. Although the plans are not legally binding, they are intended to guide all local policy and they serve as legal justification for the City or County’s decisions on proposed developments.

Fauquier’s Comprehensive Plan has eleven chapters, which focus on natural and historic resources, population and demographics, the local economy, transportation, public utilities, and community design. It also has specific chapters on the service districts, villages, and the rural areas of the County.

Cost of Community Services

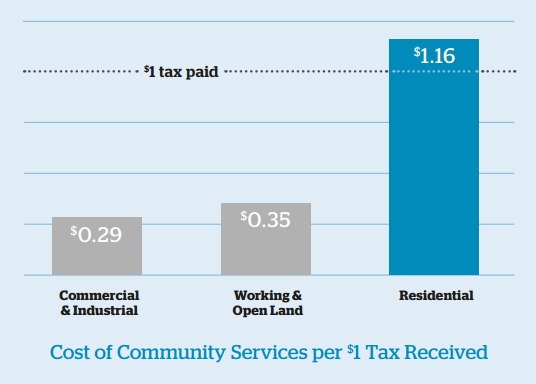

Cost of Community Services (COCS) is a fiscal analysis that determines the average cost versus revenue of different land uses—such as residential, agricultural, commercial, industrial or forestland. The analysis looks at each of these land use types, and then evaluates demands on public services (such as schools, fire protection, and road maintenance) and shows how much it costs to provide public services to each land use type.

Cost of Community Services (COCS) is a fiscal analysis that determines the average cost versus revenue of different land uses—such as residential, agricultural, commercial, industrial or forestland. The analysis looks at each of these land use types, and then evaluates demands on public services (such as schools, fire protection, and road maintenance) and shows how much it costs to provide public services to each land use type.

According to the American Farmland Trust, over a hundred COCS studies have been conducted in the last 20 years. The studies consistently show that working lands generate more public revenues than they receive back in public services. The median cost per dollar of revenue raised from working and open land is $0.35 while it is $1.16 for residential. Fauquier County is currently conducting its own cost of community services study.

Land Use Taxation

Land Use Taxation allows eligible land to be taxed upon the land’s value in use (use value) as opposed to the mar ket value, which assumes the highest value use of the land. For example, the County may value land in agriculture use at $500 per acre, while the fair mar ket value of subdividing the land for residential may be $10,000 per acre.

In Fauquier, there are four clas sifications of use value: agricultural, horticultural, forest use, and open space. Each qualifying use has its own criteria, and landowners wishing to receive land use taxation must submit an application to the County with proof of qualifications. Whenever land in land use converts to non-qualifying use or is rezoned to a more intensive use, the land is subject to roll-back taxes.

Land use taxation makes sense for farmers and other rural landowners, since they make few demands for tax- studies have been conducted funded services. It’s important to note, in the last 20 years. The land use taxation does not apply to the studies consistently show residence and surrounding one acre or to other structures on site. that working lands generate more public revenues than they receive back in public

The Composite Index

The Commonwealth of Virginia uses per dollar of revenue raised a formula known as the ‘composite index’ to determine the percentage from working and open land that a county is expected to contribute is $0.35 while it is $1.16 for to funding the cost of public educa residential. tion. The composite index is calculated using three indicators of a locality’s ability to pay: true value of real property (not use value) (50%), adjusted gross income (40%) and the taxable retail sales (10%) for the county. The result is computed per pupil and per capita for each school. Essentially, the lower the composite index the more State aid for education the county will receive.

For this formula, properties that locally benefit from land use taxation are reported to the State Department of Education at their true fair market value—not the reduced land use value. Since conservation easements permanently encumber property, they are reported at their decreased fair market value. Permanently conserved land contributes to a lower composite index, providing more money for education.

Conservation Easements

A landowner can protect specific conservation values on his or her land forever by donating a conservation easement. A conservation easement is a legal agreement between a landowner and a land trust or government agency, and it is legally recorded and bound to the property in perpetuity. The landowner retains ownership and use of the land and may convey it like any other real property, subject to the terms of the easement. Conservation easements may be purchased, such as through Fauquier’s PDR Program, or donated.

Landowners have traditionally used conservation easements as a tool to voluntarily and permanently limit development and uses on the land while ensuring continued protection of the property’s conservation values. Conservation values can include rivers and streams, historic and cultural resources such as battlefields, significant agricultural soils, wildlife habitat or natural and scenic features.

A conservation easement may qualify as a tax deductible non-cash charitable gift if it permanently protects important conservation resources and meets other federal tax code requirements. Associated tax benefits could include a Federal income tax deduction, Virginia state tax credit, and a reduction in local property taxes. For more information about conservation easements, visit pecva.org/conservation.

In Fauquier:

As of December 31, 2014, conservation easements in Fauquier County have protected 395 miles of streams, 3,544 acres of scenic rivers, 9,932 acres of historic battlefields, 50, 369 acres of farmland, and 39,256 acres of forest.

This article was featured in our Fauquier County Special Edition of The Piedmont View. You can read more of the articles online or view a PDF of the publication. The publication was issued by The Piedmont Environmental Council, in partnership with the Goose Creek Association, Citizens for Fauquier County, Fauquier Preservation Society, Northern Virginia Conservation Trust, Mosby Heritage Association and the Remington Community Partnership.