When it comes to drinking water protection, I’d argue the question facing Loudoun today is this: How much are we willing to increase development in the environmentally sensitive Transition Area? Particularly when we know the result would be a long-term reduction in water quality and increased cost to taxpayers…

In the search for answers to this question, I find it helpful to dig into the water landscape in Loudoun.

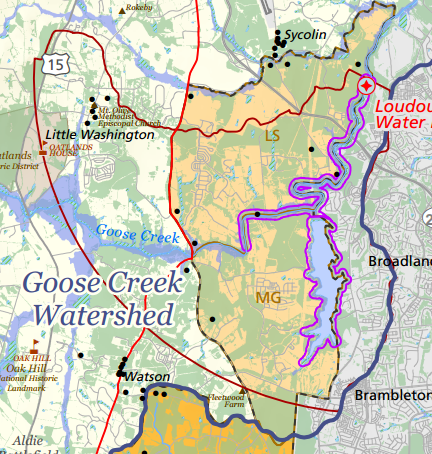

Eastern Loudoun residents on central utilities get their drinking water from three sources: the Goose Creek, Potomac and Occoquan rivers. The amount of water from each source varies and these water supplies are intermingled in the utility system.

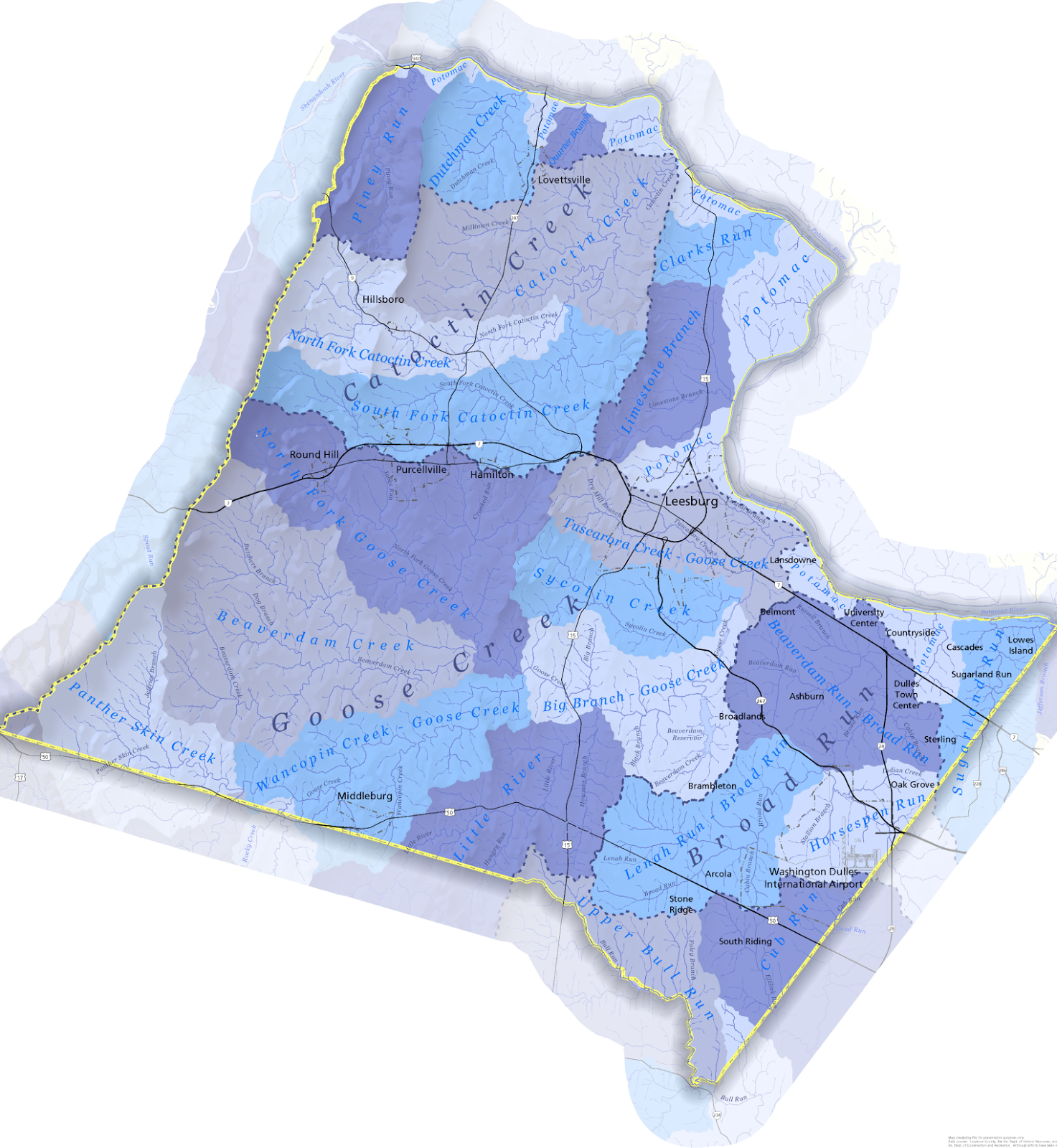

Map by PEC

The water in Goose Creek comes from the Goose Creek watershed, which encompasses almost half of Loudoun County and a quarter of Fauquier County.

- Forty percent of the land in the Goose Creek watershed is protected — either through public lands or private conservation easements.

- Small headwater streams and tributary streams run through much of that protected land. This helps keep the entire length of the stream healthier and benefits suburban drinking water customers.

- Protections far upstream are not enough to offset the impacts of development on land just upstream or adjacent to the Goose Creek reservoir and drinking water intake.

Source: The Piedmont Environmental Council

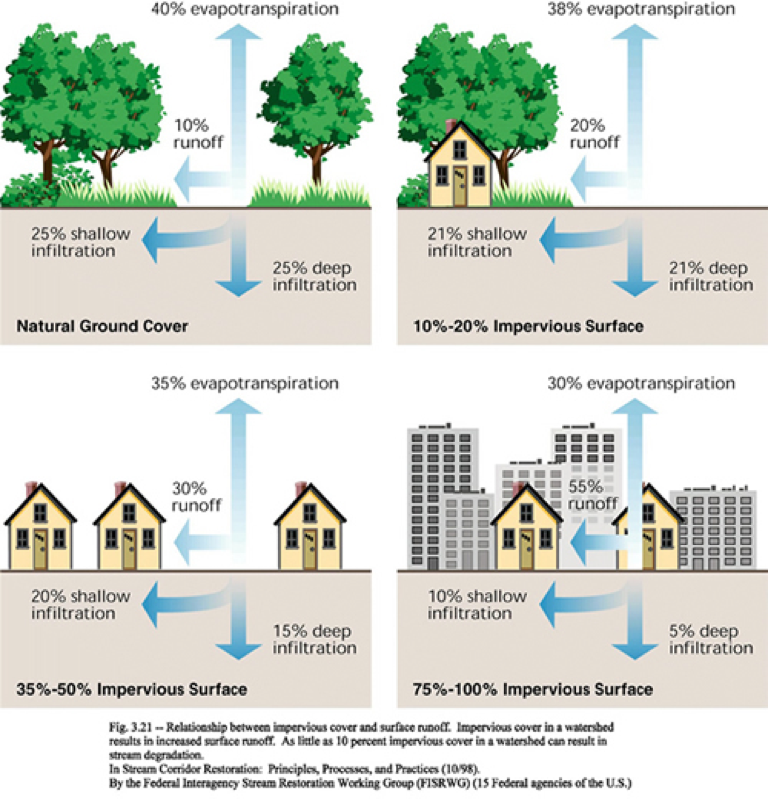

Two reservoirs, Goose Creek and Beaverdam, are part of the Goose Creek water supply system.

The Goose Creek drinking water plant (see image below) was sold to Loudoun Water by the City of Fairfax in 2014.

Pictured in the foreground is the water treatment plant in 2003, back when it was owned by the City of Fairfax. The Goose Creek reservoir is in the upper right side of the photo above the dredge fill site. Photo by Missy Janes.

Beaverdam Reservoir (see image below) is a drinking water storage facility. When the creek flow is high, water from Goose Creek is pumped into Beaverdam reservoir to be stored until the creek flow is low. Then it is released back into Goose Creek to supplement the in-stream flow and maintain a consistent supply.

Looking from south to north over Beaverdam Reservoir, March, 2003. Photo by Gem Bingol, PEC.

Looking from north to south over Beaverdam Reservoir, summer 2017. Loudoun Water is currently upgrading the dam and spillway. PEC Photo.

Looking southwest over Goose Creek Preserve to Beaverdam Reservoir in the upper left corner. The Transition Area border aligns with Goose Creek to the north of the reservoir, and along the eastern border of the reservoir toward the south. PEC Photo.

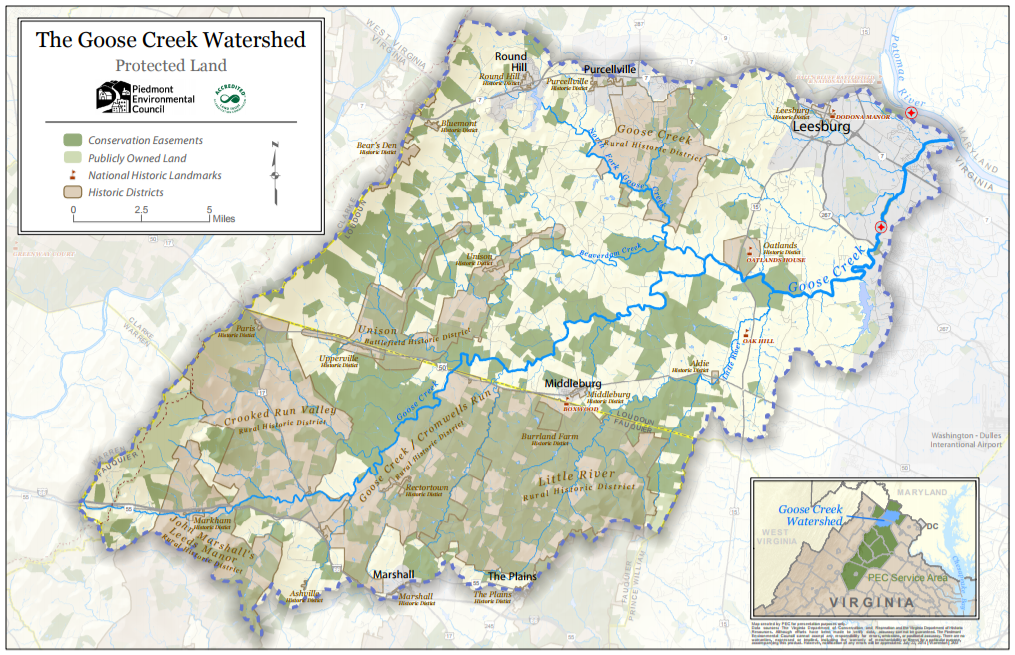

Goose Creek Reservoir (see image below) is right in the main body of the creek, and water is piped to the water treatment plant directly from the stream. The proposed True North Data site is on the upper right side, just behind the Greenway. This photo pre-dates construction of the new Loudoun Water drinking water plant.

The Transition Area is markedly different from the Suburban Area. It was planned for lower density development in part to help protect the natural resources. A photo comparison of 2003 and 2017 shows changes that have taken place in this section of the Transition Area and neighboring Suburban area. This sensitive part of the Transition Area is zoned TR-10 (1 house per 10 acres) and is still mostly open.

View of part of the Transition Policy Area & Suburban Policy Area in 2003

View of part of the Transition Policy Area & Suburban Policy Area in 2017

The Suburban area lies to the east of Goose Creek and the Beaverdam reservoir. Most Ashburn neighborhoods are east of Belmont Ridge Road (pictured just right of center in the 2017 photo).

Belmont Ridge Road lines up with the ridge separating the Goose Creek watershed from the Broad Run watershed. Most of the suburban neighborhoods pictured are in the Broad Run watershed and runoff flows to the east.

On the west side of Belmont Ridge Road, but east of Goose Creek and the reservoirs in the Suburban area, several developments were approved and built between 2003 and 2017.

- These developments increase run-off to the west and have an impact on drinking water quality.

- In order to offset the runoff impacts from neighborhoods in the suburban area, we need to stick to the planned level of development in the transition area.

In the Transition area on the west side of the Goose Creek and reservoirs, the land is still mostly undeveloped with a mix of forests and fields. There is a fairly high percentage of forest cover along the creek and also in the Beaverdam Reservoir watershed. This helps to offset the impacts of development in the Suburban area.

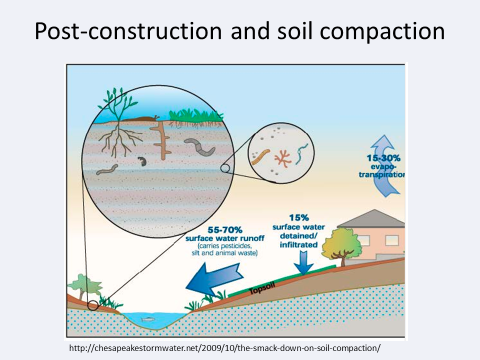

What happens if True North Data is rezoned to Office Park? The threat to our drinking water supply increases significantly, and it sets the stage for more data centers in this part of the Transition Area. With more intensive uses, our forests get stripped and replaced with hard surfaces, and run-off increases substantially.

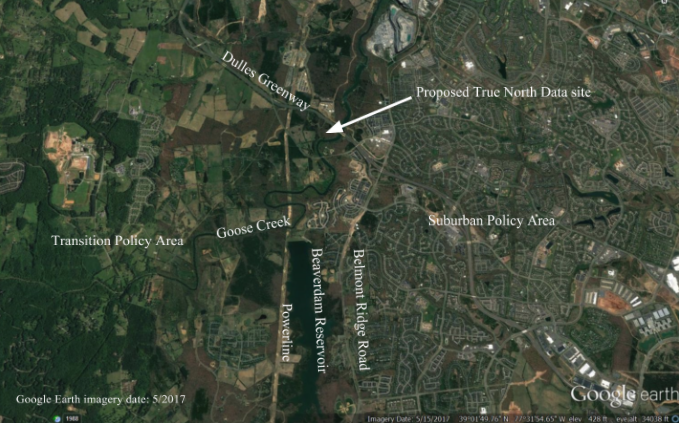

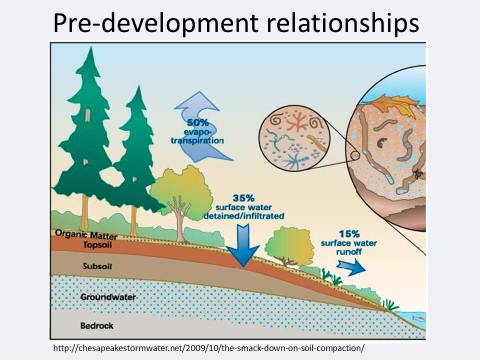

From the Federal Stream Corridor Restoration Handbook, 1998

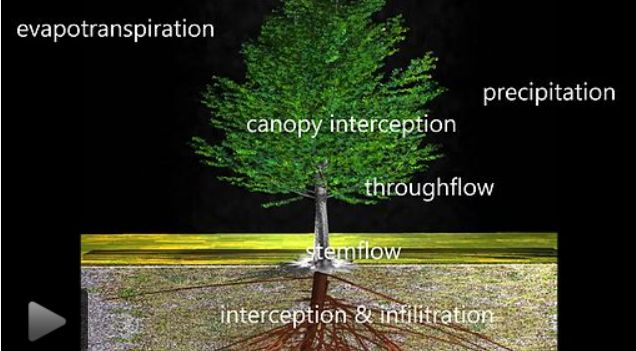

Most of the rain that falls on forested areas doesn’t run off; it gets taken up and released back into the air by the trees.

- A typical forest of 10,000 trees will retain approximately 10 million gallons of rainwater a year.

- A single mature oak tree can consume (transpire) 40,000 gallons of rain water through its roots yearly.

- Trees also intercept thousands of gallons of rain a year that mostly evaporate or slowly seep into the ground. In urban and suburban (not forested) conditions, a single deciduous tree can intercept 500-700 gallons of rainwater, an evergreen up to 4,000 gallons, which evaporates instead of running off.

(sources, American Forests and Penn State University, Extension)

When trees are cut down, streams fill up quickly with runoff rainwater that carries lots of dirt with it. The speeding water further scours the stream bed, increasing the erosion from the banks and bottom. This is what a stream looks like due to erosion:

Photo by Darrell Schwalm

With high amounts of sediment & erosion, stream water often looks like this:

Photos by Darrell Schwalm

Sediment in the water gets carried to the reservoir, where a lot of it falls to the bottom in the slower moving, deeper water, and can eventually fill it up.

- Since the Goose Creek Reservoir was constructed over 60 years ago, it has been dredged once (in the late 1990s), due to accumulated sediment.

- The dredging cost $1,688,500 to remove 58,500 cubic yards of silt, which was placed on land close to the water treatment plant.

Pictured below, the sediment from the first dredging is on the hill above the Goose Creek reservoir. With new development so close by, how often might the reservoir need to be dredged in the future? And where would the silt be taken next? It has to be treated as toxic material, so finding a site and hauling it increases the cost.

^^section source: John Boryschuk, City of Fairfax Director of Utilities in mid-2000s, personal communication

The sediment from the dredging in the late 90s was put on the hill above the Goose Creek reservoir. Photo by Missy Janes.

Loudoun County has a Reservoir Protection Zone for the land area draining to the reservoirs. It is outlined on the map in maroon and aligns with the eastern border of the Goose Creek watershed in the Suburban Area. It sets out a more protective standard for development. Nonetheless, each development contributes a new load of runoff laden with sediment, nutrients and toxins. The cumulative impacts of all the individual developments is greater than the sum of each one.

The County is charged with monitoring soil & erosion preventive measures carefully to make sure that they are properly maintained, and perform properly, so that they don’t look like this:

Photo by Darrell Schwalm

Or this:

Photo by Darrell Schwalm

But even the best maintained artificial system cannot match the protection of a forest against run-off and water quality degradation.

Loudoun Water developed a Goose Creek Source Water Protection Program in 2003 that models the impacts to the drinking water supply based on the Comprehensive Plan. It shows that water quality will be diminished as we continue to build.

This makes sense. As impervious surfaces increase, water quality decreases. (Impacts of Impervious Cover on Aquatic Systems, Center for Watershed Protection)

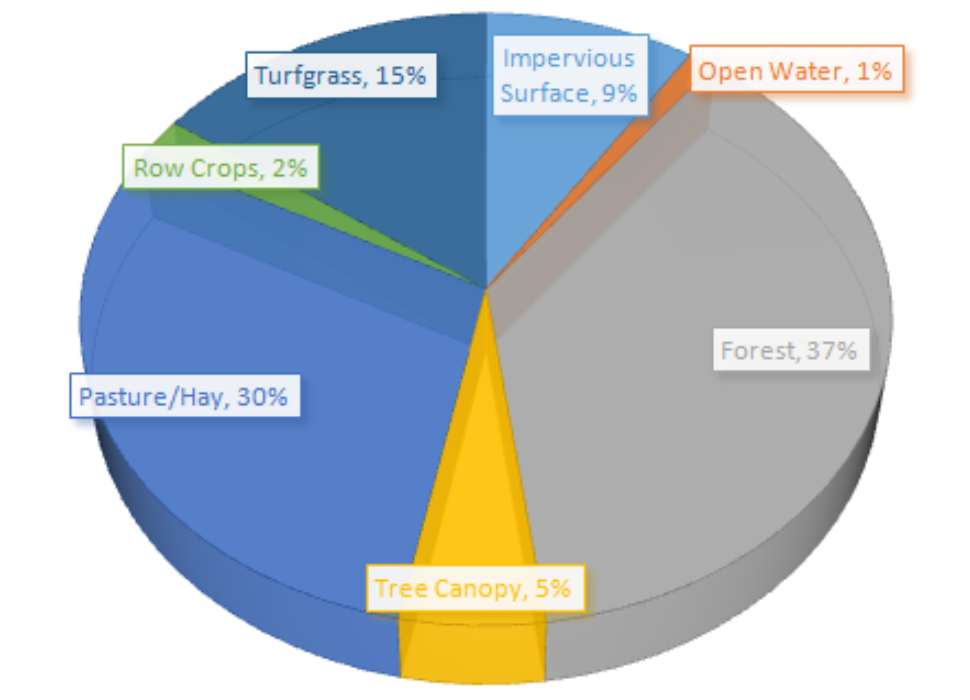

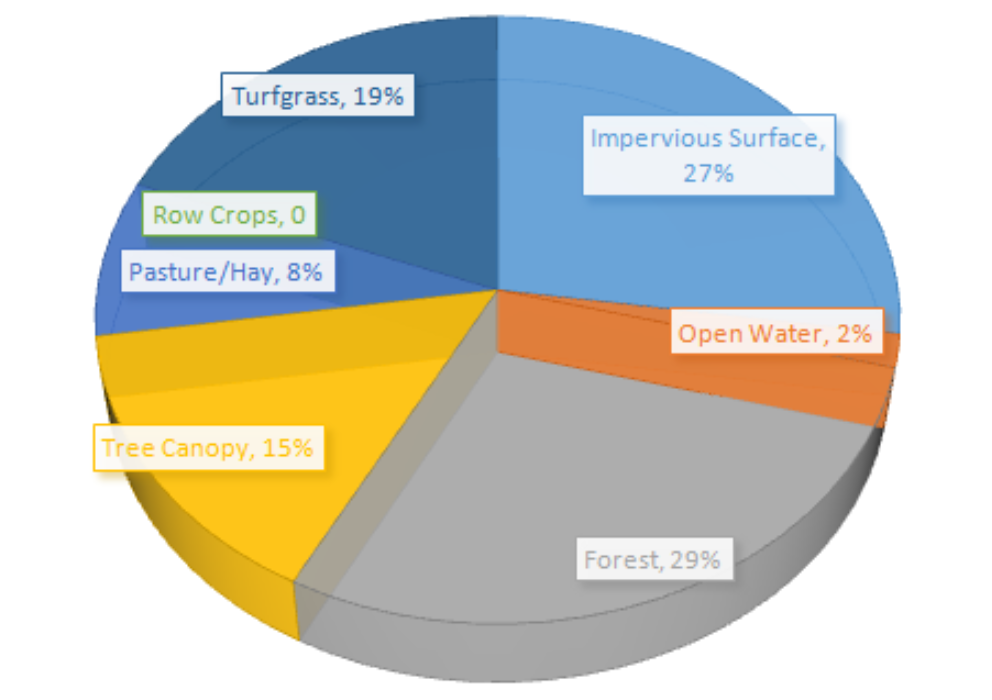

For a look at the land cover in Loudoun, I put together the following two charts using data provided by Loudoun County staff:

Land Cover Estimates for Loudoun County

Land Cover Estimates for Loudoun Urban Areas

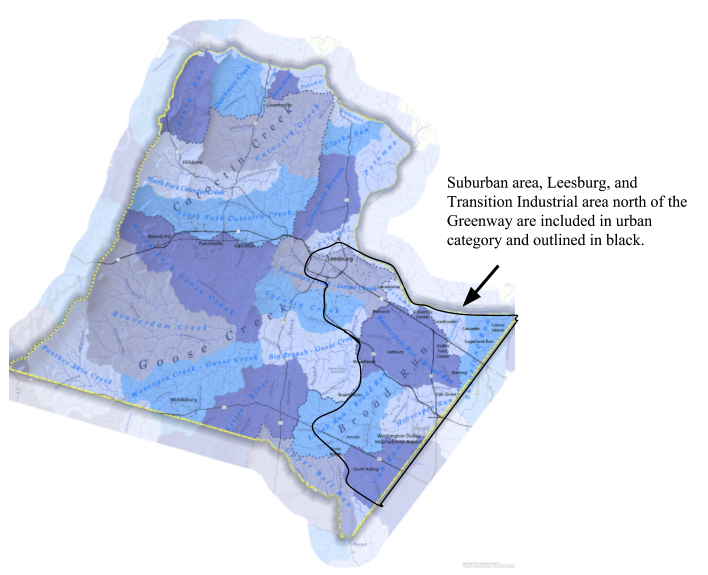

What constitutes a “Loudoun urban area” in the circle chart above?

The area circled to above is included in the ‘urban’ category.

Consider this: In 2016, in conjunction with their annual survey, the Gallup organization reported that “Polluted drinking water and the pollution of rivers, lakes and reservoirs have consistently topped Americans’ concerns throughout Gallup’s 27-year trend measuring these environmental issues.”

Of Americans surveyed in the 2017 Gallup poll:

- 63% worry a great deal about pollution of drinking water (up from 61% in 2016)

- 57% worry a great deal about pollution of rivers, lakes and reservoirs (up from 56% in 2016)

Source: http://news.gallup.com/poll/190034/americans-concerns-water-pollution-edge.aspx

Source: http://news.gallup.com/poll/207536/water-pollution-worries-highest-2001.aspx

If Loudoun residents are like those surveyed, then it would be safe to assume that they are also concerned.

Development that does not match or reduce what’s currently allowed will only worsen the problem.

In answer to the question that I posed at the top of this post, I’d suggest that it’s time we recommit to resource protection with a positive vision that honors the public interest in having clean drinking water and clean streams, reservoirs and rivers, and ensures that we are safe to fish and swim in our waterways.

~Gem

—

Gem Bingol

Loudoun Field Representative

The Piedmont Environmental Council