One of my favorite things about being a community planner is going to events and having conversations with people in informal settings, close to where they live. These gatherings tend to be a lot of fun. For example, the one I just went to had a vegan-hotdog-tasting station!

Community events are also great places to hear from residents about their everyday experiences. People are in good spirits and they have many great ideas, perspectives and inspiration. They force me to reevaluate my assumptions, which leaders and planners ought to do — and do so regularly.

This past Saturday, I had the pleasure of tabling at the third annual Healthy Streets Healthy People gathering in Booker T. Washington Park in Charlottesville, organized by our partners at the Move2Health Equity Coalition. I especially love this event because the theme aligns perfectly with my own professional focus, many attendees share my passion and it’s in a beautiful park.

Although I’m working on many projects and issues, I like to keep things simple when I’m meeting with the public. People are busy, and if they are kind enough to gift me with their time, I owe it to them to be concise. So I only had one key question that I asked everyone, which seemed like a fair exchange for me stamping their bingo card. Of course this often led to follow-up and extended dialogue, which was intentional. And I had other materials for people who were curious or wanted to go deeper.

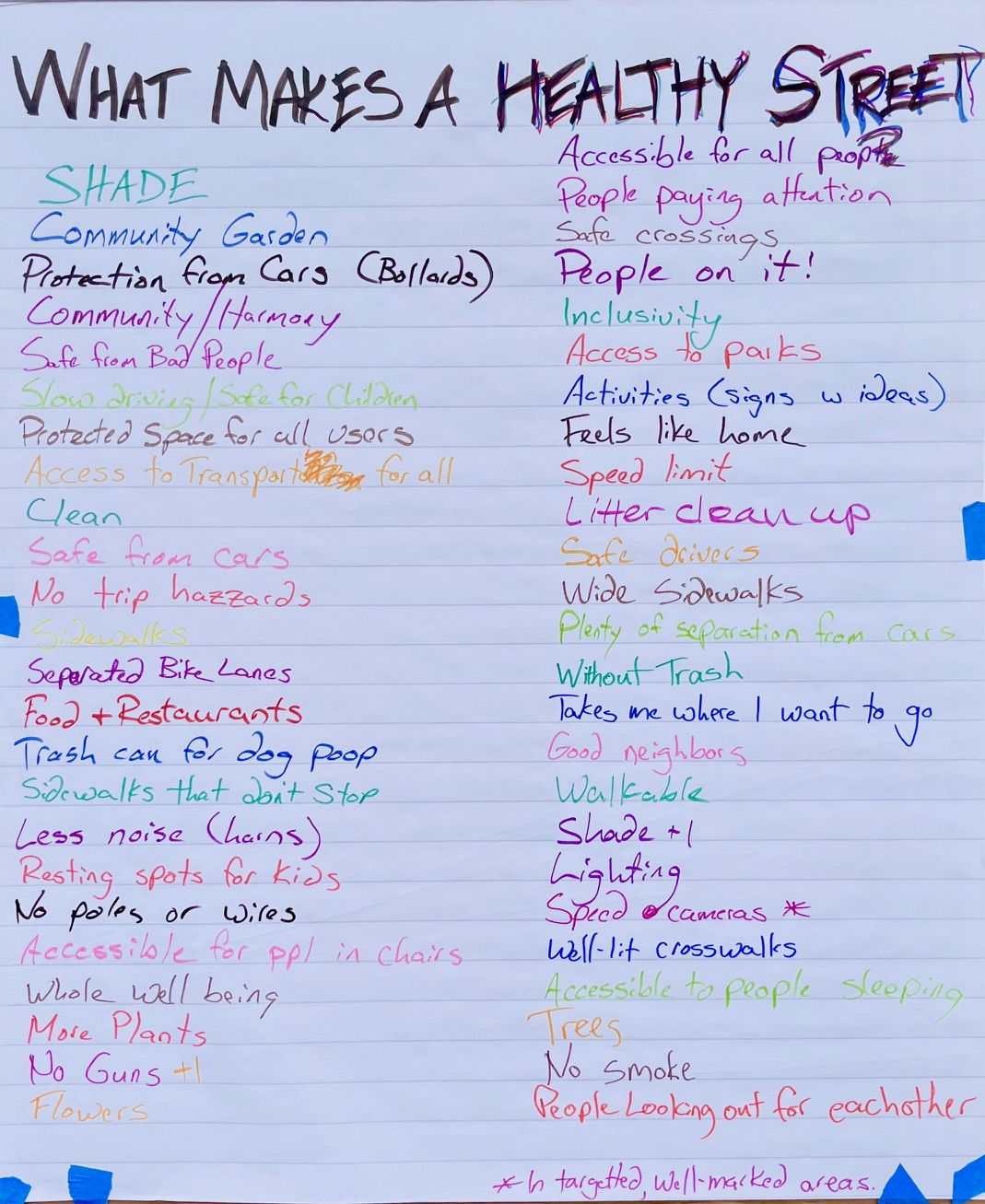

I gave everyone the following prompt: “Here we are at the healthy streets fair; what makes a healthy street?” If clarification was needed, my follow up was, “What characteristics would make the street a place that boosts you up, rather than bringing you down?” Almost everyone had immediate ideas to share and had actually given the idea some thought. Most ideas were familiar (and on point) and some made me think about my work in new ways.

Some common topics included safety, stress reduction and inclusivity. Each of these contains a world of nuance. For example, sidewalk safety might mean not getting hit by a car while walking along it or trying to cross a street. It might mean knowing that assistance is always available without being harassed by other people or by law enforcement. It could mean being able to negotiate the space without falling or being injured. Or not getting shot. And on and on; each idea merits a voluminous discussion of its own.

One conversation really stood out to me as an interesting framing, with implications far beyond the street. A woman told me that her spouse is a bus driver, who often complains that pedestrians who are focused on their phones often do foolish things for lack of attention to their surroundings. Note that she was not blaming potential victims of traffic violence: we all agree that those behind the wheel have a greater responsibility and that distracted driving is a public health challenge on par with drunk driving.

But she was asking why we can’t have an urban realm with enough appeal to be so interesting in itself that people wouldn’t feel the need to pull out their devices. That is a worthy question with implications about how we attend to one another, our spaces and ourselves.

It also gave other suggestions I heard (e.g. street art, trivia questions on little signs, foodshop windows, other people, conviviality, etc) new texture. Our conversation passed beyond the street through other spaces including classes and living rooms, which is to be expected at a health fair. But our public spaces have an important role to play.

It would be interesting for me to write a follow-up in which I compare these responses to what I learned at the same gathering two years ago when I asked attendees, “What makes a successful park?”

I entered the field of urban planning in hopes of creating a mutually-reinforcing triad of creativity, community engagement and practices that promote public health and well-being. Here was validation and a reminder that the work is urgent and anything but boring. Plantings, tiny libraries, street art and the like are not trivialities: they could save some lives.

Residents possess a wisdom that inspires good work and prevents costly or harmful mistakes. But we need to actually listen, which is not always easy. Conversations like this one, and the many others I had on that afternoon, are also fuel. They provide energy to go forward and they provide the ingredients necessary to solve the complex problems we face.

—

Peter Krebs is the Community Advocacy Manager for the Piedmont Environmental Council. His work focuses on promoting walkable, bikeable, livable communities in Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia. He can be reached at pkrebs@pecva.org