Hope Porter and Sue Scheer have been fighting to protect rural land for decades. It was in the late 1940s that Porter and her husband realized what the post-war surge in automobile ownership and long-distance commuting could mean for Fauquier County, their home—unless people stood up to protect the countryside. Together with a few likeminded neighbors, they worked to establish the county’s first zoning, when any kind of land use planning was still a rarity.

In the 1960’s, they fought off a development near Warrenton large enough for 32,500 people, called North Wales. When Sue and Julian Scheer arrived in 1965, to buy a farm south of Warrenton, they joined the fray. Sue championed—and got—a moratorium on development until a review of the Comprehensive Plan was complete. Over the years, the Porters and the Scheers worked with other formidable citizens to defend the county’s open land, again and again. In the 1990s, these citizens helped stop a massive Disney theme park—and the Orlando-style sprawl that came with it—in nearby Manassas.

When a new way of protecting land became available—voluntary conservation easements on private property—it caught on in Fauquier, starting in the early 1970s.

“We knew that… all zoning can be thrown out, and that easements were the only sure thing,” Porter says—because conservation easements protect the land in perpetuity.

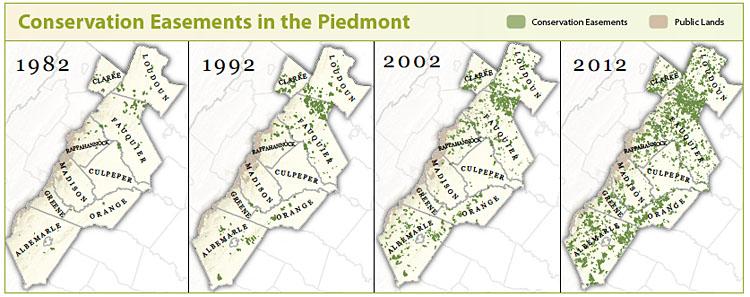

In 1972, grassroots activists in Fauquier joined with others from Loudoun to Albemarle and founded PEC—with a mission to keep this nine-county region beautiful, historic, environmentally healthy, and agriculturally productive. Forty years later, among the results is an extraordinary 349,000 acres of land that are protected forever by conservation easements, including 12,200 acres that were protected last year.

“The love of the land”

Porter protected 47 acres on the slopes of Wildcat Mountain early on, and later, a 200-acre farm near Marshall. The rolling farmland where she currently lives—her childhood home, near Warrenton—was protected by members of her family.

The Scheers donated an easement on their 421-acre cattle farm in the 1990s, and they’ve also influenced a number of their fellow farmers in southern Fauquier to pursue conservation. After Julian’s death, the family, along with PEC, established a fund in his memory to support land conservation. This fund works closely with Fauquier County’s Purchase of Development Rights Program to preserve working farms in the Cedar Run watershed. (So far, nearly 26,000 acres, or 10% of the watershed are protected, counting both public and private conservation land.)

Porter says that she wanted to help keep agriculture strong in Fauquier. “I just think it’s going to be terribly important to maintain some land on the eastern seaboard that’s not covered with houses,” she says, “that can produce crops and have cattle.”

Scheer, who served on the local Planning Commission and the PEC Board of Directors, adds that they wanted to preserve rural land because development would lead to a spike in taxes, to pay for new schools and infrastructure. With higher taxes, families that had lived on the land for generations could be forced out—and the land they sold would go up in more houses.

Porter also confesses a “selfish” reason for conserving land. “I loved the countryside,” she says. She got to know it on horseback—riding with the hunts or roaming over the hills. “When we were children, in those days, we had the freedom of the countryside,” she says. “Every day of our lives we weren’t in school, we would be riding over the countryside.”

Scheer, too, sees an abundance of practical reasons for land conservation—you need dairies near cities, you need clean streams to feed water supplies—but her most basic motivation, as a farmer living close to the land, was her connection to it. “It was the love of the land,” she says.

349,000 acres, one family at a time

People’s feeling of connection with the place where they live can be a powerful force. With nearly 349,000 acres under conservation easement, private landowners have now protected a full 15% of the land in this region. Parks and other public lands cover another 8%—so that, altogether, nearly a quarter of the land is protected.

PEC’s long-term goal is to achieve one million acres of protected land in the Piedmont—the Piedmont Reserve—while directing new development to towns, cities, and growth areas.

“When you think about the way that private land conservation works—one family at a time, making decisions about the future of their property—it takes a long-term vision to see how it can come together,” says Heather Richards, PEC’s Vice President for Conservation and Rural Programs. “As PEC celebrates its fortieth anniversary, we’re starting to see that vision take shape.”

Conservation easements in the Piedmont now protect:

- 163,000 acres of prime farmland

- 159,000 acres of forests

- 1,400 miles of streams and rivers

- 8,000 acres of wetlands

- 22,000 acres of Civil War battlefields

- 90,000 acres in historic districts

- 97,000 acres along Scenic Byways

- 103,000 acres visible from the Appalachian Trail

PEC makes this level of success possible by advocating for strong conservation policies at the local, state, and federal levels; building public appreciation for the benefits of conservation; doing extensive outreach to landowners; and offering one-on-one assistance to landowners during the easement process. PEC is also expanding our role as a full service land trust. While in the past, we have typically partnered with other land trusts (usually state agencies) as easement holders, going forward, we are accepting more easements, in order to expand landowners’ options and make more conservation possible.

A wild forest

Last year, Frank and Eleanor Biasiolli protected their 120 acres of forest land in Greene County, less than a mile from Shenandoah National Park. While most conservation easements allow for agriculture and timber harvesting, the Biasiollis wanted to preserve their land as a wilderness area, an old-growth forest in the making. They worked with PEC and the Five Hundred Year Forest Foundation, as co-holders of their easement, to pursue this vision.

Frank says, “I wanted for it to always be like it is—well, even better than it is today.”

The Biasiollis, who live in Charlottesville, bought this land some twenty years ago to satisfy their need for city-country balance. She needed the city, and he needed the country. But, they both feel fortunate to have spent so much time in these woods, where they have a small house near the remains of an old mill and a log cabin, on the banks of the Lynch River. Behind it, forests rise steeply up the slopes of County Line Mountain (on the border of Albemarle and Greene), and slender creeks rush down to the river.

“I just love being out here,” Frank says. They wanted to protect it, “so other people can experience this same kind of thing.”

“There’s a sense of awe when you’re in forested areas,” Eleanor says. “You get to see all the diversity that’s out there. There’s just so much to learn… Once you’ve lived in an area where you can learn to appreciate and love the environment that you’re in, you see that there is a purpose for all the different things. It’s life. It’s not to be cleared down and paved over.”

Sometimes, they witness this life in moments that surprise or amaze them. For example, Frank says. “One time there was a bear, high up in a tulip poplar… When he recognized that I was around, he started coming down. He just dropped like half a bear’s length, and grabbed. Dropped and grabbed.” Another time, Frank saw a fox hunting in the snow; it pounced, then ran with its catch up the ridge. He once watched a wasp that was preying on a beetle; the beetle was too large to carry, so the wasp dragged it along in small hops. One day, he saw an American eel in the river; it was after the dam was removed at Woolen Mills, he thinks, that the unusual fish could travel so far upstream.

Their experience inspired the Biasiollis to protect their land as a sanctuary where human disruptions will be minimal—a place where the trees can grow vast and the animals live as they will.

“It’s still here.”

When Hope Porter and Sue Scheer look back on their work in Fauquier, their measure of success is this: “It’s still here.”

The two friends can list other Northern Virginia counties that are “gone”—developed beyond recognition. The land that they have spent decades working to save—the wooded hills and sloping fields before the Blue Ridge, the bountiful farmland with streams that flow toward Cedar Run—is still here.

Scheer says this is because “There have been so many active citizens in this county… The citizens’ organizations, including PEC, have made the difference. You talk to other people from other parts of the country and they say, How do you preserve it? It’s because the citizens have responded.”

Sometimes that means taking part in the public process. Other times, it’s about a landowner’s decision to protect their piece of the earth—like the Biasiollis’ mountainside, the Scheers’ wide pastures, and the rolling croplands surrounding Porter’s home. For generations, this land will be here.

This story was the feature article of our Spring 2012 Member Newsletter, The Piedmont View.